Africa’s third-highest peak hides in a rugged and remote Ugandan mountainscape of friendly guides, rich wildlife, and zero peak-bagging crowds.

It was raining monkeys. Colobus monkeys, that is, flinging themselves at least 50 feet through the air from tree to tree, sending a cascade of leaves down on our heads like confetti. Between the running river and acrobatic primates thrashing through the treetops, the rainforest of Uganda’s Rwenzori Mountains was nearly deafening.

This was just one of the many unexpected moments experienced while trekking in the Ugandan mountainscape. It was a journey full of unknowns through knee-deep muddy bogs perched between 10,000 and 14,000 feet, across open moorlands, and up steep glaciers to its highest summit on Mount Stanley's crown of Margherita Peak (16,763 feet), the highest point in Uganda and third-highest in the continent.

Chuck Graham

I had good luck convincing friends Craig Fernandez, 52, and Danny Trudeau, 65, to accompany me in February on my fifteenth trip to Africa. The Rwenzoris have been on my mind since 1990, when the film Mountains of the Moon released. Starring Patrick Bergin and Ian Glen as British explorers, Sir Richard Francis Burton and John Hanning Speke, the film follows the men on an epic quest to discover the source of the Nile in 1857-58. It was a brutal journey full of hardships that would eventually turn the two explorers into bitter rivals.

The Rwenzori Mountains were mentioned on multiple occasions in the writings of Burton and Speke as they searched for the Nile’s source. After several more difficult expeditions into Africa’s central interior, Speke was credited with the discovery of Lake Victoria, the true source of the Nile, although a small portion of the Rwenzoris also feeds that river.

Chuck Graham

Later, in 1906, Italian explorer Luigi Amedeo (aka the Duke of Abruzzi) led a team on the first successful ascent of Margherita Peak, naming it after Queen Margherita of Italy. Today, the mountain range is a designated World Heritage Site.

Peaks and Valleys

The Rwenzori Trekking Services website didn’t lie. It sternly warned potential trekkers and climbers the terrain is steep and difficult with lots of muddy bogs, and that there was a certain fitness level required to complete one of their many treks.

After summiting both Mount Kilimanjaro (twice) and Mount Kenya, it was clear to me that reaching the tallest peak in the Rwenzoris would require even more effort. These lesser-known mountains include six of Africa’s 10 highest summits—with Margherita Peak being third to only Kili and Mount Kenya in all of Africa.

For me, the mud was the biggest surprise. On Kilimanjaro and Mount Kenya it was confined to the dense tropical rainforests near the mountain bases. That wasn’t the case in Rwenzoris. The only spot along the climb where we didn’t encounter huge swaths of mud was up at Margherita Camp (14,700 feet), the final camp before our summit push.

Chuck Graham

From the moment we left Trekkers Hostel in Kilembe (4,785 feet) with our guides, Samuel and Rogers, we began our ascent through the incredible vegetation zones for which the Rwenzoris are known. The walk leading into the rainforest was brimming with smiling, laughing, and playful Ugandan kids. My digital camera became all the rage when I played back those beautiful, curious smiles.

There’s a lot of wildlife in the Rwenzori Mountains, but spotting any of the forest antelopes, reptiles, birdlife, and raucous primates was another matter. The rainforest is dense and wet. A steady rush of creeks and waterfalls helped conceal the sounds of the forest.

Chuck Graham

Transition Zones

Beyond the rainforest, thick stalks of bamboo came in handy as we ascended the narrow spines of so many rolling ridges. They provided sturdy handholds when the ground became steep and slippery. It felt like we were trekking the back of a sea serpent, its rolling spine never ceasing until we reached our first overnight at Kalalama Camp (10,276 feet).

What was most impressive during this time were all the mountain guides and porters lugging huge packs, bags of food, and other essential items to the camps. Not one of the porters was without a smile on the ever-changing terrain, and they always offered a friendly greeting even when the elevation was at its most challenging.

We were in a transition zone at Kalalama Camp, where bamboo started to wane and the tall canopy of the heather forest hovered above our first significant plateau. Usnea beard lichens clung to the heather trees, offering much-needed shade on a precipice where cozy cabins awaited several tuckered-out trekkers.

But fatigue was soon forgotten with our first sunset and the next morning’s sunrise, a fireball of orange rising above Uganda’s sweeping eastern savannah. The dawn of a new day in the Rwenzoris was thoroughly enjoyable while holding a cup of hot tea and a brimming bowl of porridge with honey and chunky peanut butter—fuel for the trek to our next camp.

Chuck Graham

Of Boardwalks and Ladders

The long stretches of muddy bogs were something to behold, especially above 12,000 feet. The guides and porters, doubling as trail crews, had constructed long sections of boardwalks above some of the worst of the bogs, and also built ladders up and down the most challenging ascents and descents. We were trekking above the treeline, leaving wisps of the heather forest in our wake while forging ahead through the stunning moorlands of the Rwenzoris.

The throng of otherworldly vegetation that cloaked those daunting peaks sometimes made us forget about the mud entirely. Every now and then we would stop and gaze out at the utterly breathtaking mountain panoramas. Giant lobelias, forests of giant groundsel trees, endless mounds of tussock grasses, Saint John’s wort, and other vegetation dominated the mountain landscape.

Chuck Graham

Above 13,000 feet, we reached Bugata Lake, the first of several alpine lakes and an excellent place to spot some of the impressive birdlife in the range. More than 1,000 species of birds have been documented in Uganda, representing over half of the species found on the entire continent. One of those is the brilliant scarlet-tufted malachite sunbird, endemic to the high-altitude zones of East and Central Africa. Its curved beak, forked and elongated tail, and shimmering feathers make it stand out against the vegetation, especially around the nectar-rich giant lobelias.

Well above Bugata Lake, we took several moments to soak in the epic views from Bamwanjara Pass at 14,685 feet. Here, we had the first real look across a deep valley toward Margherita and the high peaks of Mount Stanley, Mount Baker, and Mount Speke, with swirling plumes of wispy clouds ascending skyward. Then it was a slow, muddy, 2,000-foot descent, leading around a couple of tranquil lakes and down a series of well-placed ladders. From there, it was a 500-foot ascent to Hunwick’s Camp at 13,114 feet.

Chuck Graham

Into the Mist

Hunswick’s Camp is situated on a plateau overlooking a boardwalk that crosses a valley splitting two vegetated peaks with three lakes. The giant groundsel forests are tall and clustered, leading to Margherita Camp. It was our shortest day of trekking, and we were grateful to rest for the ascent to the summit.

The high camp was busy with climbers finishing their summit push—resting, eating, and packing up for destinations unknown. All the eating cabins en route were equipped with wood-burning stoves and Margherita Camp was no different. It was a great place to huddle up and stay warm, sort gear, and tell stories, while the guides and porters chimed in with their own tales of the Rwenzoris.

Chuck Graham

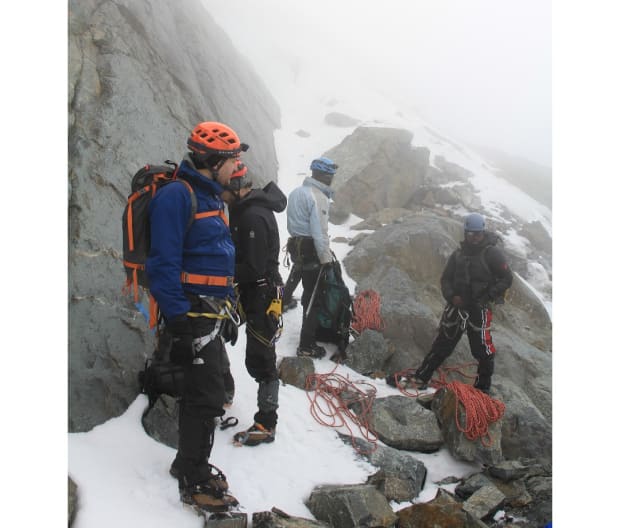

Up at 1 a.m., headlamps burning bright, we began our long summit push in cloudy but unusually warm conditions. I’ve always theorized it’s better to ascend in the dark because you can’t see how far you need to go. Plus, the darkness conceals how much more difficult the terrain might become. I relayed my theory to my companions, and they bought into it with a subtle nod or a reluctant thumbs up as we slowly traversed our first glacier in the dark.

Still in crampons, we scrambled across a rocky section toward Margherita Glacier. Samuel warned this glacier was steep—a 70 percent grade—and it would take nearly two hours to traverse. Tied together and in good rhythm, we pressed on, while visibility deteriorated to less than 25 feet. Because a series of crevasses crisscross the glacier, Samuel and two of the other lead guides set ice screws into the glacier and fixed lines for everyone to follow. Steadily we traversed, giving each crevasse a wide berth, with visibility all but nonexistent at this point.

Once we reached the overhanging portion of the glacier, visibility slightly improved. From there it was a snow-covered, rocky scramble to the summit. If it had been a clear morning, we would have been able to gaze across the valley toward Bamwanjara Pass from where we stood two days earlier. Instead, we settled for milling around the summit post at 16,763 feet.

Chuck Graham

A Wild Descent

Sometimes it’s tougher going down than heading up, and that was clearly the case in the Rwenzoris. Our downward journey was caked with slippery mud fed by the onset of heavy rain. From Hunswick’s Camp, it was almost a 2,000-foot ascent to the top of Oliver’s Pass (15,000 feet) through narrow gorges to each plateau where giant groundsels soaked in all the moisture, acting as natural water catchments. I slipped repeatedly from those smooth, thick leaves.

During the arduous descent from Oliver’s Pass, we did manage to enjoy some nice diversions. One of the best was the brief sight of a red duiker, a small, stocky but shy mountain antelope. Once back in the rainforest, the head porter Paul and I veered briefly on an alternate route for more bird sightings. That produced a cinnamon-chested bee-eater and a red-chested sunbird.

Chuck Graham

Further along, Paul spotted a pair of blue monkeys in dense vegetation, tight roping with utter aplomb on a narrow branch. They were across the river, but when spotting us, they hammed it up with a ton of noise either by their own vocalizing or thrashing through the rainforest.

Danny, Craig, and I had made a special request of the guides and porters. We wanted to see a chameleon, which initially felt like spotting a dime at the bottom of the ocean. They came through in a pinch, showing us two different species within a few feet of each other. The first was a three-horned chameleon—which scaled Rogers’ sleeve.

Chuck Graham

The second one, a giant chameleon, put on a real show, flashing at least six different colors before blending into the trees like only a chameleon can. In an instant, it had vanished entirely in the rainforest of the Rwenzoris, a mountain range brimming with natural wonders from its highest peaks to its smallest inhabitants.

To learn more about trekking in the Rwenzori Mountains visit Rwenzori Trekking Services and Rwenzori Mountaineering Service.

from Men's Journal https://ift.tt/62oPXUx

0 comments