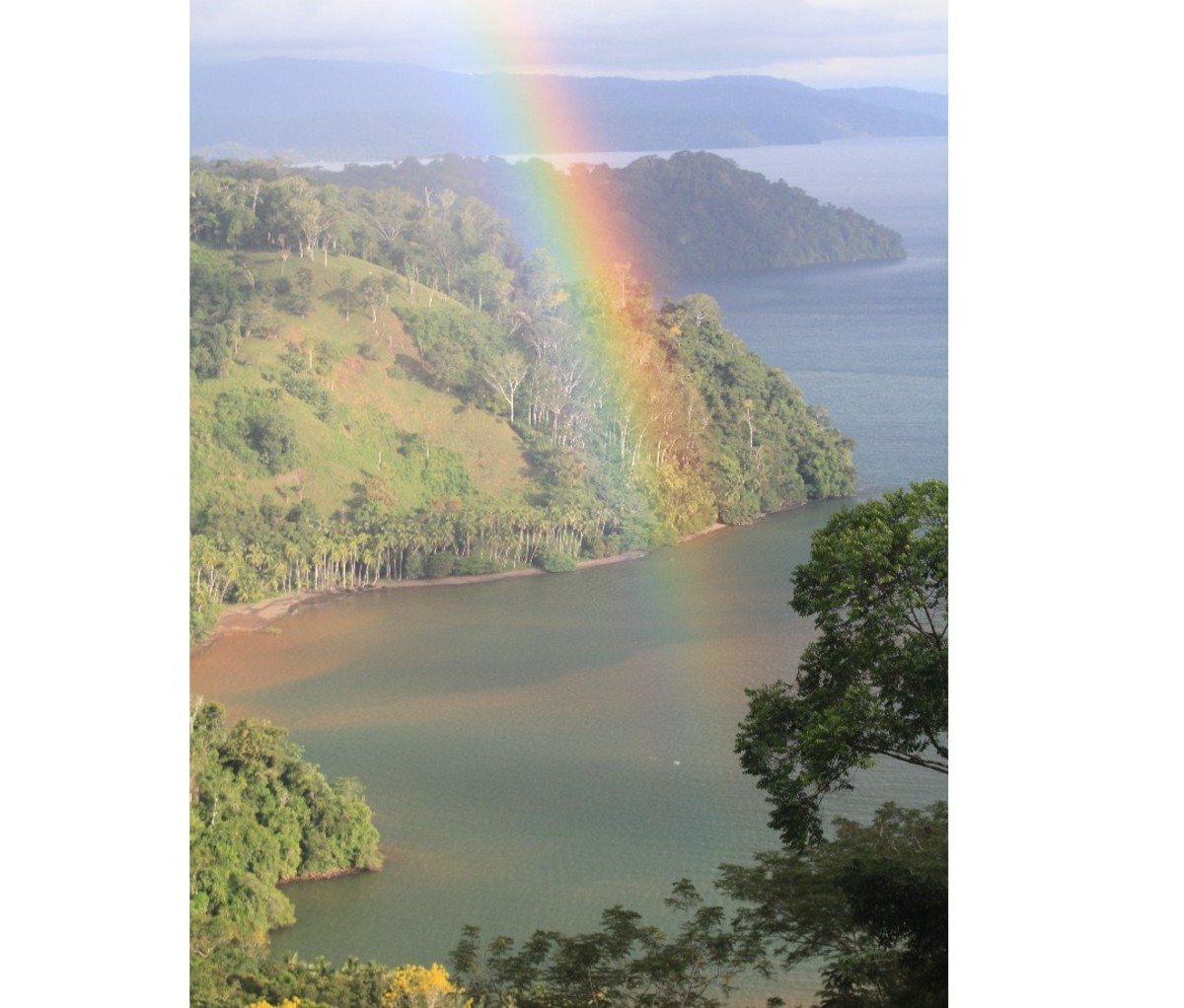

Costa Rica’s Corcovado National Park Is an Ecological Playground Like No Other

In the rainforest of Corcovado National Park, tucked on the Osa Peninsula of Costa Rica, bushels of leaves float down from a green canopy so dense it blocks out the sun. It’s not from strong gusts of wind. Instead, all of that ruckus in the towering sabre and cashew trees is coming from a thoroughly determined northern tamandua, also known as a collared anteater.

Tamanduas are nearly blind, but equipped with thick, long claws; a 16-inch tongue; and a powerful tail that wraps around tree trunks and branches for stability. This enables these tree-climbing aficionados to extract ants and termites from cavities in precarious positions throughout the rainforest.

Marine biologist Holly Lohuis and I are in the middle of a five-day trek through Corcovado National Park, which National Geographic considers one of the most biologically intense areas on Earth. We want to see as many species as possible, so binoculars and camera gear are always at the ready. Within the first few miles of our trek, Corcovado is living up to its reputation.

The tamandua continues to cause a ruckus, stirring up other fauna, birdlife, and insects concealed in the rainforest, most of which we’d never see without an expert. Marco Umana of Osa Wild has been guiding in Costa Rica for five years. An avid birder with a keen eye, Umana has seen 725 of Costa Rica’s 935 bird species and even accomplished a “Big Year” in Costa Rica, which means spotting as many avian species as one can in a single country in 365 days. In Umana’s case, he nailed down 649 species in 2017 alone.

Minimal Impact

Corcovado became a national park on October 24, 1975. It’s the largest in Costa Rica, covering 164 square miles within the largest primary rainforest on the American Pacific coastline. It also includes one of the last remaining areas of notable lowland tropical forest on the planet.

To access the heart of Corcovado National Park, all visitors are required to be accompanied by a guide. There’s no wiggle room there, but it’s to anyone’s benefit, as the guides are reliably incredible, enthusiastic, and extremely knowledgeable. Holly and I guesstimate we would’ve only seen 10 percent of the wildlife we encountered if we’d been on our own.

Corcovado does not allow camping. Trekking is from ranger station to ranger station, where everyone sleeps in bunk beds beneath mosquito netting on raised platforms. Meals are included—and no one will be going hungry in Corcovado. The national park doesn’t want anyone cooking, so all food is prepared and served buffet-style at the Sirena Ranger Station.

After spending a couple incredible nights at Danta Lodge, Holly and I begin our trek in the northern sector of Corcovado at the Los Patos Ranger Station. We trek 13 miles in the mud, scrambling up narrow canyons while crossing several tranquil rivers to the Sirena Ranger Station—the park’s main hub, near the coast. Depending on how long visitors stay at Sirena, days are filled with several guided hikes. Guides are armed with guidebooks, spotting scopes, binoculars, and the E-bird app as they work extremely hard to locate the rich flora and fauna thriving in Corcovado.

Water Is Life

Walking on water is one thing. Dropping from a tree or a rock and covering five feet per second across its surface is an added feat reserved for the aptly named Jesus Christ lizard. When the green basilisk lizards feel threatened, they move lightning fast, sprinting upright across water with relative ease. Its unique, biblical capability comes in handy when eluding throngs of predators in Corcovado’s steamy rainforest.

Whenever near a water source, you’re virtually guaranteed to see these sleek, two-foot-long reptiles dashing bank to bank along serpentine streams and rivers, as well as black-mandibled toucans, spectacled caimans, American crocodiles, and tiger herons.

During our trip, Umana nabs all four of Costa Rica’s species of monkeys, which is a real hoot. Actually it started with a bellowing howl that momentarily drowned out all other sounds in the rainforest. The sound of howler monkeys dominated the canopy among an added chorus of white-faced capuchin, spider, and squirrel monkey calls.

At one particularly broad river mouth, we watch a common black hawk, tucked in the fork of a dead tree, successfully dismantle a large, freshwater crab. Patiently waiting below is an opportunistic crested caracara (another type of raptor) ready to scarf up the remains. Nothing goes to waste in the rainforest, as one species benefits another.

Above the birds of prey are a breeding pair of scarlet macaws enjoying the blossoms in a huge cashew tree. They first drink the water caught inside the blossoms, then consume the blossoms themselves. These neotropical parrots light up the canopy of the rainforest like no other bird with a stunning plumage of multi-colored feathers. That and their raucous RAAAK, RAAAK resembles what a prehistoric pterodactyl might have sounded like millions of years ago. They can live up to 75 years, and Corcovado National Park is an important bastion for this iconic rainforest species.

No Sunscreen Required

There’s one more massive river mouth to cross before leaving Corcovado National Park, reaching Carate, and catching our ride back to our car in Puerto Jimenez.

In this last two-mile stretch, Holly nearly steps on a well-concealed brown vine snake. I’d never seen her jump so high and move so quick, but the inhabitants of the rainforest can do that to you.

It also occurs to me we haven’t used sunscreen the entire five days—and didn’t need to. The always-shady rainforest took care of that. We’re sorely reminded of it in Carate when we emerge from the rainforest into the blistering sun. Diverted by a pair of breeding scarlet macaws underneath the canopy of a lone cashew tree, we crack open ice-cold Coca Colas and take long glugs from the bottles.

If You Go

General info: Pacific Trade Winds offers a broad range of Costa Rica travel intel from accommodations to attractions, plus a trip planning guide.

Where to stay: Nestled on the northeast fringe of Corcovado National Park on the Osa Peninsula, Danta Lodge is the perfect home base to relax and begin a trek.

Guided trips: Founded by a pair of local naturalist guides, Osa Wild runs exceptional multi-day tours throughout the park, handling all logistics without a hitch.

from Men's Journal https://ift.tt/I65MO1k

0 comments