On October 13, 29 runners began one of the most remote races in the world, the inaugural Snowman Race, organized by the Kingdom of Bhutan. The five-day, high-altitude stage race isn’t just a feat of endurance; its purpose is to highlight the dangers of climate change in the small Himalayan kingdom, which is sandwiched between two of the world’s biggest polluters: India and China.

Bhutan is a high-alpine country experiencing rapid change. Glaciers are melting, flooding valleys and destroying homes and villages. For context, Bhutan is roughly the size of Switzerland, or the states of Massachusetts and New Jersey combined.

“We’re not going to sit on our hands doing nothing,” says Lotay Tshering, prime minister of Bhutan. “We will fight climate change. Our protected areas are our lungs. Bhutan is one of only three countries that is carbon negative, along with Panama and Suriname.”

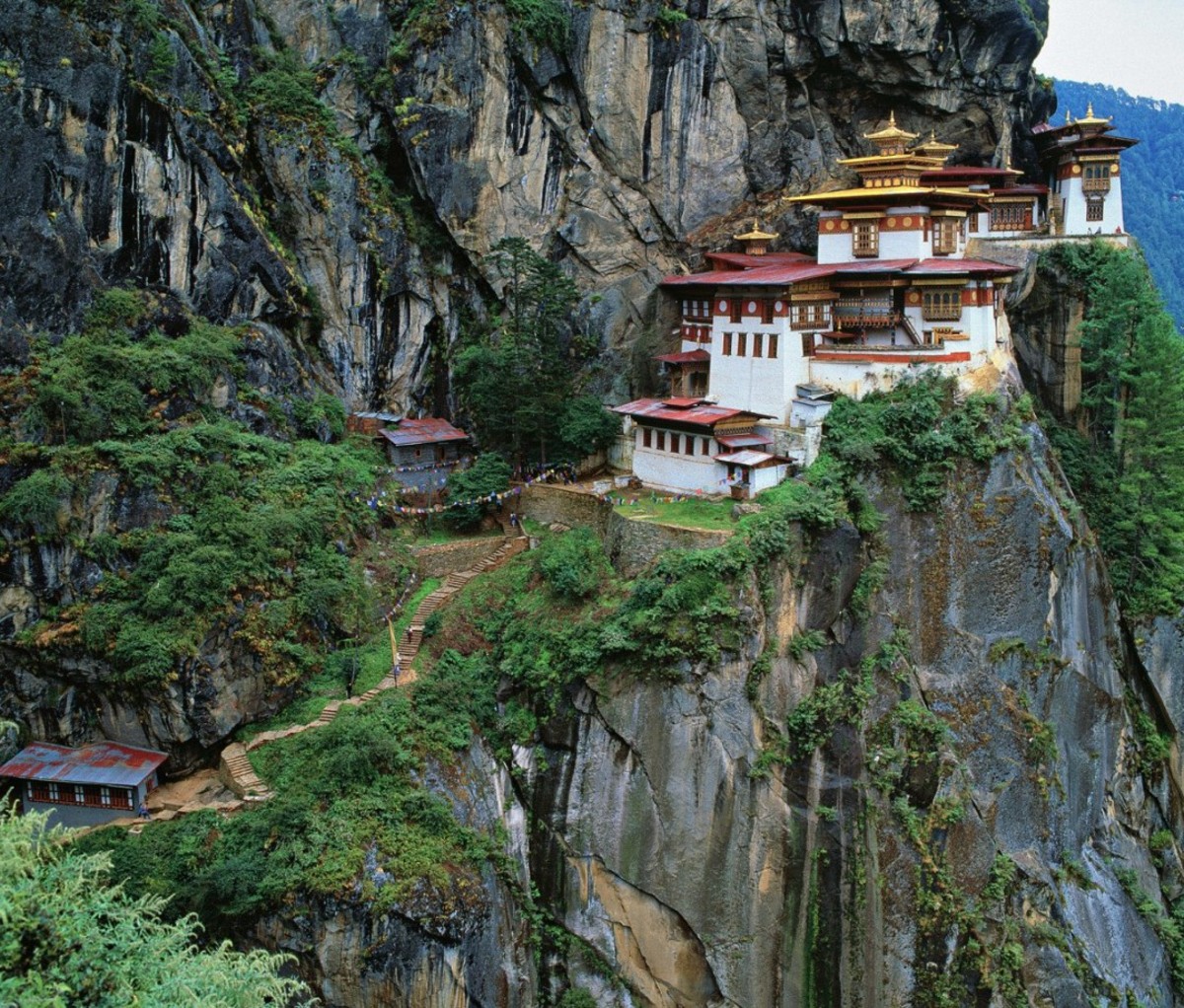

Snowman Race follows the famed Snowman Trek for 126 miles (203km), from the town of Gasa to the town of Chamkhar in northeastern Bhutan. The race courses through diverse terrain from jungles to fragile, high-altitude ecosystems to remote mountain villages. The Snowman Trek is arduous, typically taking adventurers three weeks to complete. But very few do. To put it in context, more people have summited Mount Everest.

Snowman Race in a Nutshell

The 29 ultrarunners of this year’s race comprised nine Bhutanese runners and 20 international athletes—from the U.S., Canada, Japan, Australia, France, Germany, Singapore, Tanzania, Switzerland, and the UK—including past winners of Marathon des Sables in Morocco, a Seven Summits finisher, and multiple winners of prestigious 100-milers.

Due to the high elevation, 12 competitors dropped out over the course of five days, some of which were evacuated via helicopter due to altitude sickness.

The trail is technical and incredibly high in altitude, with a crest of 17,946 feet and an average elevation of 14,500 feet, almost as high as the summit of Mount Whitney, the highest point in the continental U.S. The route crosses 11 mountain passes, through the remote Lunana area of nomadic herders, near the world’s highest unclimbed mountain, Gangkhar Puensum, then through two of the largest parks in the country, Jigme Dorji National Park and Wangchuck Centennial Park.

Snowman Race has no road access along its entire length, including any aid stations or mandatory evening stops. This requires all the aid station workers to hike into their resupply spots days ahead of the start. The route was marked with flags, but darkness made navigation challenging and competitors often used GPS to stay on course. Racers were also required to carry mandatory equipment including a backpack with sleeping bag, food, water, rain gear, a warm jacket, hat, gloves, and first aid.

Racing With a Greater Purpose

With a population of fewer than 800,000 people, Bhutan doesn’t get the media attention or global clout its larger neighbors do. The country offsets more than double the 2.2-million tons of carbon dioxide it produces each year, but still sees the negative impacts from neighboring polluters by way of floods, faster run-off from glaciers, and unpredictable storms and heavy rains.

Bhutan has made major progress within its borders, prioritizing its citizens’ health through free education, free healthcare, investments in electric transportation, sustainability and waste programs, and free electricity to farmers, but Bhutan knows it can’t solve climate change on its own. That’s where Snowman Race comes in: It’s part sporting event, part political message to the rest of the world.

“The people who live at the threshold of melting glaciers contribute the least to climate change but are the first to see its devastating impact,” says Bhutan Queen Jetsun Pema. Bhutan has almost 700 glaciers that are melting at an accelerating rate and 17 glacial lakes, which are classified as dangerous. If one of the natural dams were to break, a disaster like Lugge Tsho—where 17 million cubic meters shot down the valley, destroying homes, farms, and killing 21 people—could repeat itself.

The climate change message was not lost on the racers. “We saw firsthand these changes,” says American runner Luke Nelson. “Footprints of glaciers that had receded with large moraines, not filled with ice. I saw the people and the threat they live with every day.”

After three days of rain in late September—less than a week before race participants arrived in-country—a landslide destroyed several houses in a mountain village in Bhutan, killing five people.

“I have spent years working in the climate and conservation space,” Nelson adds. “I’ve seen the impacts of climate change over and over again, yet this is the first time I’ve seen a government taking it so seriously and asking the rest of the world to join them.”

from Men's Journal https://ift.tt/PdWUoLk

0 comments