I’m just hoping it won’t make me a statistic,” says Vitaliy Musiyenko from across my dinner table in Mariposa, CA, just outside Yosemite National Park. The 35-year-old climber is referring to his voracious passion for doing new routes and ropeless climbs in the nearby Sierra Nevada range, while performing endurance feats and Fastest Known Times (FKTs) that boggle the mind. Musiyenko’s magnum opus is the Goliath Traverse, aka “the Goliath,” an endurance climb so over-the-top that he actually had to coin the name Goliath himself.

He’s vaguely heard of a few other attempts on this route—none of which came even remotely close to completion. “Supposedly one team starting from the north got about as far as Palisade Crest before deciding the rock was too loose and not worth the risk,” he says. Musiyenko’s colleague Alex Honnold, of Free Solo fame, calls Goliath “the longest and most adventurous ridge traverse I’ve ever heard of. Literally miles of rock climbing.” The mere thought of it, adds Honnold, leaves him “horrified, repulsed—and inspired.”

At the table, Musiyenko is donning a chalk-dusted jacket that hides his solid frame. Bloodstained athletic tape is still wrapped around his hands from logging 2,000 vertical feet of Yosemite climbing over the last couple of days. Just a little extracurricular activity while here to share his Goliath Traverse experience with me. A journey so long that it fits on two maps. So arduous that only portions of it have been tackled by the world’s best, luring in mountaineering luminaries like Peter Croft and Conrad Anker.

“That’s what attracts us to do hard things,” Musiyenko says matter-of-factly. “It’s that they’re hard.”

Yeah. That’s quite the understatement with the Goliath Traverse, a 32-mile ridge crossing in the High Sierra that ascends 80,000 vertical feet (nearly three times the height of Everest) and, in doing so, crosses 60 peaks. News of Musiyenko’s solo completion of this monster last August stunned the elite climbing world. Crazier still, by combining ultra-running, free-solo rock climbing and bare-bones camping above 13,000 feet, the Ukrainian-American climber did it in just eight days in one continuous push without a resupply.

“Alpinist and Climbing magazines say it’s the biggest traverse that’s been done in the Western Hemisphere as a technical route,” Musiyenko says, not boastfully. It is what it is. Naturally, the first question is: What was the worst part?

“Thunderbolt Peak on day five,” he says on cue. “That was the low point.”

He pauses for a moment, as if letting some very shitty memories of Thunderbolt Peak on day five barge unchronologically into the frame of his Goliath Traverse story—before gently shoving them back in their place with a quick we’ll-get-there summation.

“I mean—if I blew it on Thunderbolt Peak, I knew I would die.”

The Goliath Traverse consists of two massive 16-mile legs along the Sierra Crest—the Full Monty Palisade Traverse and the Full Evolution Crest Traverse. On the climbing scale, both traverses are classed as 5.9 (challenging) and Grade VI (technical, committing). As for the human scale, the Full Monty had never been completed due to its length and sheer difficulty. Only a few climbers have managed to make it through all of Full Evolution, including Musiyenko from a previous climb—who’d back then called it the hardest thing he’d ever done. Last August, he was set on stringing these two behemoths together in one go. To most of his climbing peers, this was unthinkable. To Musiyenko, linking up two of the most jagged subranges of the High Sierra connected by a pass just seemed “like a pretty logical next step.”

Over eight days, this logic will require him to log 10,000 vertical feet of elevation gain daily, largely on imposing, crumbling terrain. Between summits, he’ll need to navigate huge slopes of talus-strewn ridgeline with both speed and agility.

Well before this second bid, Goliath was Musiyenko’s white whale. During a first attempt in 2016, he made it about a third of the way through before bailing—reluctantly. He would’ve pressed on, he says, had it not been for a nagging feeling that he’d die if he did. Later, he would find out that fellow elite climber and friend Julia Mackenzie had perished from a fall on Mount Haeckel the day before Musiyenko himself had climbed it.

“The Goliath became my number one priority last year,” says Musiyenko, who crammed in a year of anxious, meticulous preparation between ER nursing shifts. “I was obsessed,” he confesses. “But I knew I had to approach it with hesitation, fear and respect because if you get too cocky…”

Overcoming long odds is what Musiyenko has done from pretty much the get-go. Born in Belarus shortly after the 1986 Chernobyl nuclear disaster, he was exposed in utero to the fallout which would plague him with a chronic eczema-like skin condition. When he was 5, his parents divorced and he moved with his mother to Kharkiv, Ukraine, and later to San Francisco. At age 14, he got his first job, at Domino’s Pizza—and by 16, he was 300 pounds and struggling in school.

Joining his high school football team (“to get my ass in shape”) and powering through painful shin splints, Musiyenko would hone his signature claw-to-the-finish-line drive. Later, he’d apply it to climbing as well as nursing school. Putting himself through college, he worked double shifts as a security guard, often sleeping in his car between round-the-clock commitments. He kept this up for years.

In 2010, Musiyenko and a co-worker scrambled up 14,505-foot Mount Whitney—a three-day epiphany during which he caught the climbing bug. Joining a Planet Granite gym, he trained rigorously over the next dozen years. Today he lives in Visalia, CA, works as an ER nurse and is an expert first ascensionist. He’s climbed hard, technical ice and rock routes from Alaska’s Denali to Patagonia’s Cerro Torre. But his 150 first ascents have focused mainly on his backyard, the Sierra Nevada, where he has penned a soon-to-be-published, three-volume climbing guidebook. All of this culminates in his boldest move yet—the Goliath Traverse.

Ascending out of 5,400-foot Taboose Pass Trail Head in the Owens River Valley, the Goliath climbs steeply and starkly into a saw blade of 13,000- to 14,000-foot Central Sierra mountains. After removing his shoes and fording a raging mountain stream just to reach the start of the ridge, Musiyenko assesses the road ahead from the top of Cardinal Mountain—the first summit of numberless peaks (but 60ish if you’re counting) he’ll need to cross before the finish line. “You look down off the ridge, and you’re like, whoa—this is where it starts to get difficult,” he says. From here, Musiyenko swiftly notches summits two and three on the south and north peaks of Split Mountain.

The next day, he climbs Mount Prater, Mount Bolton Brown, Ed Lane Peak and The Thumb. This is followed by eight more 13ers on the third day, followed by a dozen pinnacles that are part of the famed Palisade Crest on the fourth—where Musiyenko experiences his first seriously hairy moment.

“I’m between two giant rocks with a massive drop-off on both sides, and have to execute a dynamic cross-step to get through,” he recalls. Grabbing hold of a granite fin he’s about to lurch to the other side just as a gust of wind barrels into him like an invisible rogue wave. “It hits me so hard my foot swings out into space. Luckily, I’m able to hold on. But that’s a real moment right there,” he says.

Free solos in consistently brutal winds at 14,000 feet are now interspersed with dicey, slow-going scrambles over “kitty litter rock,” as Musiyenko describes it. Even worse along this leg are “columns of shit glued together that can collapse on you at any moment if you try to stem on them,” he adds. Musiyenko’s final peak of the day is 14,153-foot Mount Sill, where ferocious gusts force him into a protected nook to set up his bivy. Here he’ll rely on a 0.85-pound quilt to ward off the cold from a pack weighing in at just 33 pounds. That’s 33 pounds for absolutely everything.

Day after day, the sunup to sundown climbing regimen routinely features treacherous terrain. But the nights are no kinder. Seeking flat spots along the exposed ridgeline, Musiyenko endures the frigid off-hours by warming up with pushups before crawling into his wafer-thin quilt. Wearing every single layer he has, his sleepless brain swirls with harrowing moments behind him—but especially with what lies ahead.

The next morning, Musiyenko awakens with intense pain, puffy eyes, swollen hands and aggravated tears in his meniscus that have caused his knee to puff up like a softball. It’s day five—aka “the low point”—but he’s not there quite yet. That happens after clambering up Polemonium Peak and North Palisade to the route’s crux—14,009-foot Thunderbolt Peak—arriving like a midday nightmare with some of the traverse’s meanest, most exposed technical terrain.

Heading up Thunderbolt he forms a crude self-belay by looping a sling around his waist, lassoing a horn with his 6mm static line, wrapping his heel around a summit block and mantling to reach the summit. The descent is a dizzying rappel down a precipitous 2,000-foot drop.

“This is where everything really starts falling apart,” says Musiyenko, whose rope gets stuck while rappelling, forcing him to reclimb a portion of the mountain. Then, as he’s moving toward the next peak, a washing machine-sized boulder rolls out from under his foot. Slammed to the ground, he sprains his ankle and severely scrapes his bicep. “I’d already sprained both of my ankles earlier,” he says. “But after that fall on Thunderbolt Peak, I’m like—is this where the shitshow takes over my climb?”

It’s at this point, Musiyenko confesses, that he momentarily contemplates aborting the mission. From here, it’s just a three-hour hike back out to the road. “I can feel my body looking for a way out,” he says. Still, he rules out a retreat.

“Regret. I don’t wanna live with it,” he explains. “This is exactly where I bailed during that first attempt. I know I’m hurt, but I also know I’m healthy enough to keep going. No way am I walking away from this unless I have an injury that needs, like, medical attention.”

During the last three days of the climb, wildfires blazing in the distance add their own sort of hell to the mix. “Every day is as hazy as you can imagine,” Musiyenko says. “Your body hurts. You’re exhausted. And now you’re breathing fucking smoke.”

After ascending another eight mountains on the following day, Musiyenko can barely bend his severely swollen knee. “At this point, I’m getting pretty worried I may be permanently injured,” he says. “Honestly, I just want to be done with this thing.” The near-death march carries on with Mount Powell, Clyde Spires West and then aptly named Crumbly Spire, where rocks higher than three stacked refrigerators can tumble almost just by looking at them the wrong way. “This is the worst rock I’ve ever seen,” says Musiyenko, who then hobbles over the summits of Clyde Spires East, Mount Wallace Mount Haeckel and Mount Darwin.

“At this point, I’m very close to zoning out,” he recalls. Relentless discipline pushes him forward—as well as a long-held belief and observation he won’t let himself forget, especially right now.

“People tend to give up whenever things get really tough and the odds start to feel almost insurmountable,” he says. “When you’re at that point, you just have to keep remembering that this is actually the whole point. It’s supposed to be this hard. You’re meant to face adversity and work through it with every inch of your mind and body.”

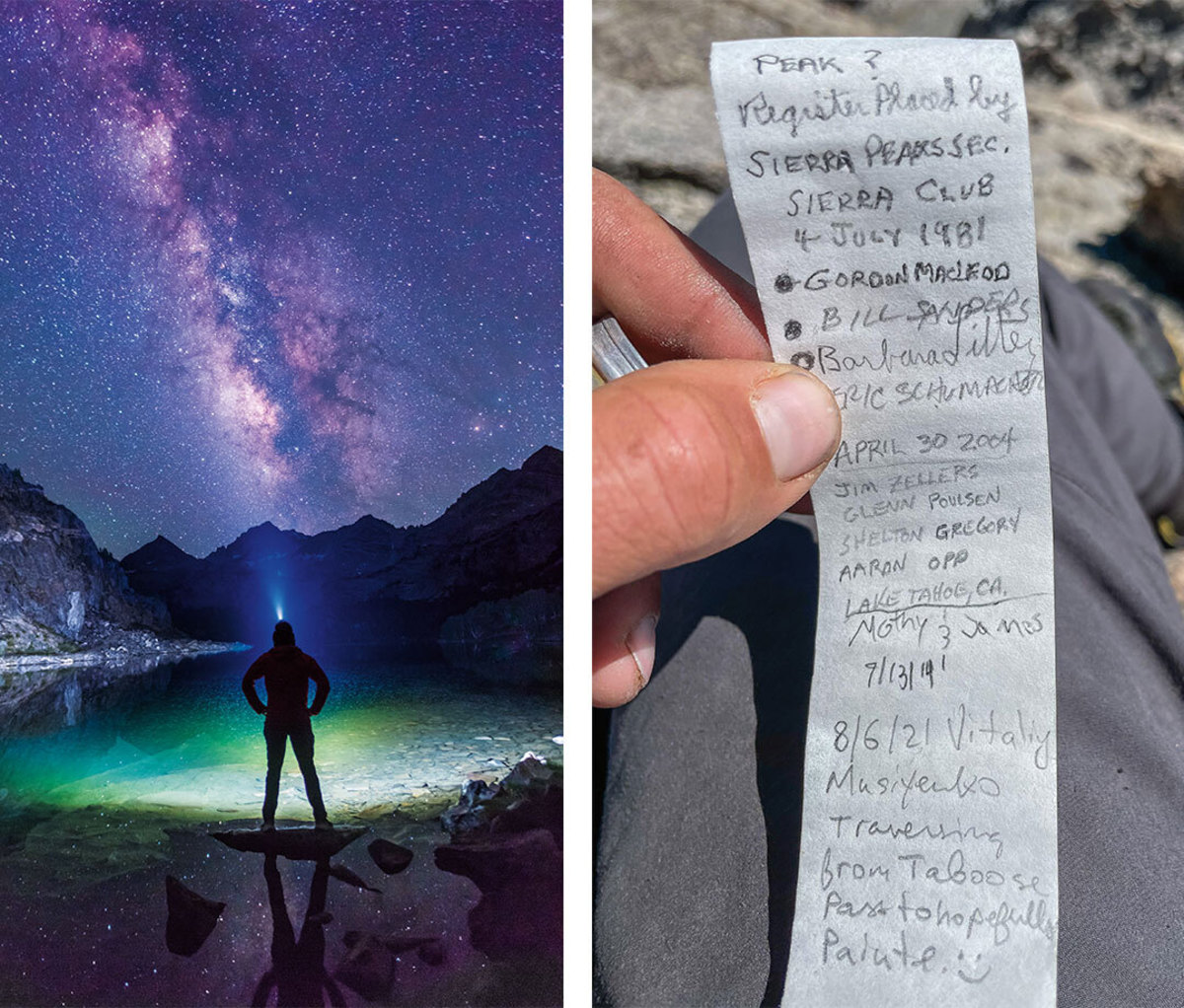

On Musiyenko’s eighth and final day, every inch of his body (and mind) aches. With a nub of a Snickers bar and three gummy worms left to eat, he pushes over more mountains—Tom Ross, Lamarck, Keyhole Plateau, Keyhole Plateau North—and eventually the final, nameless 12,600-foot summit of the Goliath Traverse, simply marked “Peak” on the map. It overlooks Piute Pass and the trail that leads him out. He reaches his car, parked there like a mirage, leans against it and sobs for 10 minutes.

“I’m feeling liberated from this multiyear obsession,” he says about those tears. “I’m excited too, of course, but mainly it’s this relief that I’ve made it through. Going into something this long and difficult is totally overwhelming, but you can’t lose composure when you keep getting smacked,” he adds, tapping into a favorite Mike Tyson quote about how everyone has a plan until they get punched in the mouth.

Soon after our meeting in Yosemite, Musiyenko starts prepping for his first trip to Nepal, where he hopes to either complete a new route on Mount Nuptse (25,791 feet) or repeat the massive 8,000-foot Moonlight Sonata route on the peak’s southeast buttress.

“We want to do it in a seven-to-nine day round trip,” he tells me. “Though the probability of succeeding on something like that is slim to none.”

Yeah, right.

from Men's Journal https://ift.tt/ukX2S7m

0 comments