Some ideas have legs. Less than five months after John “Bobby” Shackelford, a 25-year-old New York City bicycle messenger, hatched a plan for a 1,100-mile ride paralleling the historic Underground Railroad, he arrived in Mobile, AL, ready to start pedaling. Along with four friends, his aim was larger than a self-indulgent sufferfest. Instead, the cohort planned to use their journey as a tool for awareness and activism.

“We felt the momentum,” says Shackelford. “We’re all having conversations about race right now and we didn’t want to miss out. We knew we had to do it this year.” Early in the 2020 pandemic, while doing the research for his friends’ next big ride, Shackelford realized that no adventure cycling films he’d seen had representation for people of color. “There was nothing we could relate to,” he said. “So we decided to do it ourselves, to show that these types of trips are for everyone, regardless of your background or skin color. We want to show that bikes can provide freedom for anyone, even kids from the hood.”

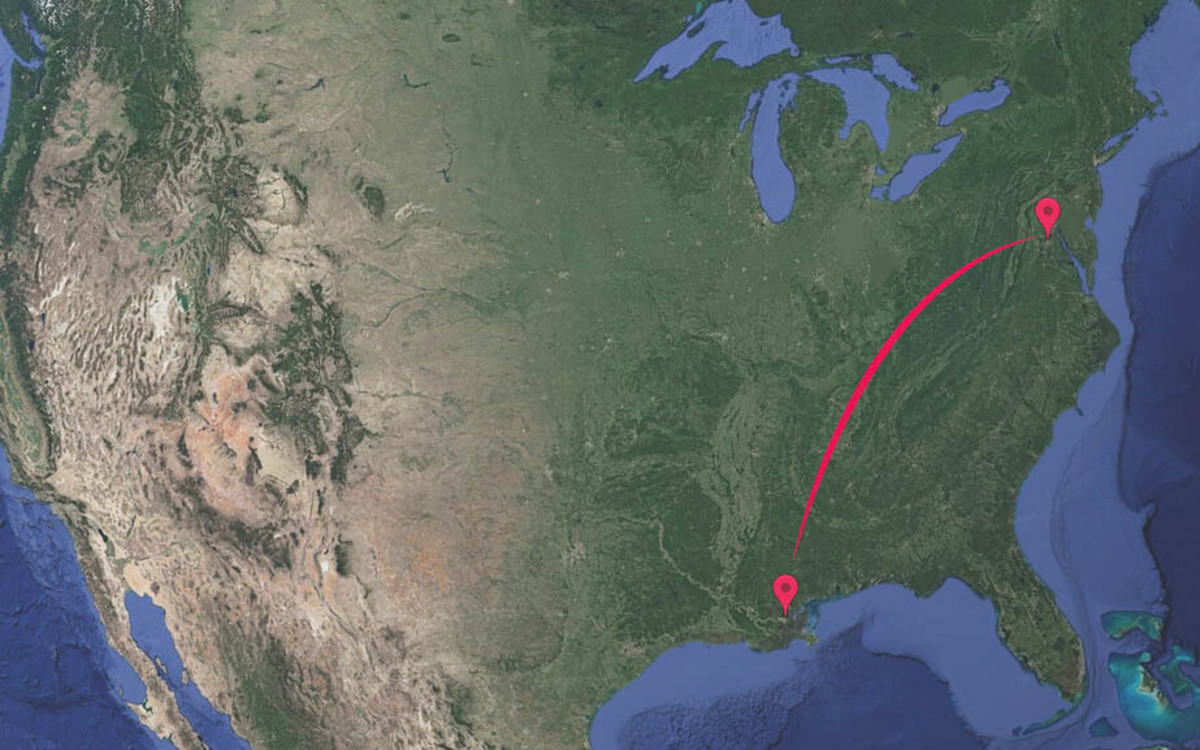

Shackelford and four companions departed Mobile on September 26 and arrived in Washington, D.C., nearly three weeks later. Retracing the path of the underground railroad, they connected historically significant locations including Selma, Montgomery, Winston-Salem, Richmond and Jamestown, to learn about and share pivotal moments in Black history, slavery, freedom marches, and ongoing persecution.

“Without a bike, I may not have gotten out of my neighborhood in southeast D.C.,” said Shackelford. “I wanted to draw this connection— that bikes are a modern form of freedom. I wanted to document our journey and show the struggles like bad weather, long days, and modern-day racism.”

Using bicycling as a tool to engage and give back (the UGRR team donated bikes to dozens of kids along the way), Shackelford spearheaded the trip and brought together a small film crew that acted as a support group during the ride. The project grew in scope as brands and donors came on board, which asked the question: What is the path from slavery to freedom and are Black people free today?

To learn more about the project, MJ sat down with Shackelford and Edwardo Garabito, another rider in the crew, to ask them a few questions about their three weeks in the saddle.

Underground Railroad Ride 2020 from Jon Lynn on Vimeo.

MEN’S JOURNAL: Where did the idea come from?

BOBBY SHACKELFORD: We plan at least one or two tours each year. We’d never done anything this big, but it’s not our first bikepacking trip. We started digging around for ideas, something to get stoked on and nothing came to the forefront. Nothing we could relate to. Nothing spoke to us. I thought of riding the underground railroad and it snowballed from there. We made a teaser, got a lot of encouragement, and watched it grow. It quickly went from a small thing to a big thing.

EDWARDO GARABITO: I’m good friends with Bobby and we’ve known each other for a long time. We have a history of doing big tours together, but nothing of this size. Originally I wasn’t going to be on the ride, but another rider dropped so I was brought in late. I’m really grateful I got the opportunity to be part of it. A month and half after I got the offer, I was in Alabama ready to ride. It was so fast. I didn’t do a ton of training, I wasn’t riding a lot at the time.

What other bike trips have you guys done together?

BS: I’ve done a euro tour from Helsinki to Latvia, a two-week trip that was supported. We also did a self-supported ride from D.C. to Niagara Falls a few months ago. That was different and more challenging, suffering with all that weight on the bike.The longest anyone had done was about 600 miles before this.

Tell me about the crew: How well did you guys know each other?

BS: I knew everyone well except for Carson. He was our mystery rider. Our dynamic was really solid. Of course, everyone had bad days and good days but no one complained or quit or said they were too tired. Everyone toughed it out.

EG: Rashad Mahoney is a racer and bike messenger from Baltimore. He’s a very mellow guy. Richard Carson races cyclocross and also is a messenger from Indianapolis. He’s fast, lovable, and cool as hell. Alex Olbrich works in a D.C. bike shop and was one of our best navigators. If it wasn’t for him we probably would have wasted a lot of time. I’m also a bike mechanic in D.C. for an exclusive shop. I’ve been a mechanic my entire life and was able to help out with the bikes on the trip, which was nice. Bobby is confident and stubborn. He was the leader of the group and could ride a bike for years without stopping.

Why did you guys decide to do this now?

EG: Because of the climate and everything going on in the world right now. There’s a ton of media coverage for people of color and about police reform. We thought it was the perfect time to bring this message out. We wanted to show that anyone can do these long treks. We wanted to show something that no one else has. We wanted to inspire people. To show there are people of color doing big rides.

BS: This needed to happen. It felt like my responsibility. The industry says it is lacking diversity so I wanted to create it. I can say it all I want but if I don’t put it into action what’s the point. I needed to get the ball rolling and this is the start. I needed to show people how to take action. We just wanted to show real representation to a larger crowd. I guess you could say it’s my calling if you believe in that type of thing.

Tell me about the ride: How long was it and what were the key stops along the way?

We started in Mobile, Alabama, where the last slave ship landed in the U.S. Then we head to Selma, the location of Bloody Sunday, and then to Montgomery, Alabama, where the civil rights marches took place. We visited the lynching museum in Montgomery (National Memorial for Peace and Justice), then on to Winston-Salem, stopping at some of the oldest African American churches in the country and the first Black communities in North Carolina. Then through Jamestown, home of many plantations, and on to D.C.

EG: We got to see Africatown, one of the last places slaves were freed. In Jamestown we saw where the first slaves lived. In Selma we saw where MLK led the civil rights march. And a lot of museums, too. We were doing 70-110 miles per day and rode for 15 days total, with a few rest days in between. Took us about three weeks to complete. Honestly, it was pretty hard. The terrain was brutal and hot, often in the upper 80s and humidity. We always had to be prepared with food and water, not knowing where we’d find the next town. There were some crazy hills in Virginia with long miles that we just had a muscle through.

What was it like having a film crew with you?

BS: It was our first time doing this and was challenging at times, mostly lining up on the schedule often dictated by filming in good light, especially in the mornings and evenings. We did a lot of interviews, got to meet a bunch of historians, activists, and people like Ahmaud Arbery’s family. We got to learn from all of them. We worked with the film crew to weave in cycling, mostly by using bikes to connect all these locations. We wanted to show how bikes can bring anyone freedom. The bike crew and production team were both super diverse. I didn’t want it to be an exclusive Black thing. I wanted a mixed group. Native Americans, Latinos, white and Black. We all need to solve this together.

EG: The production team was a group of people that came together at the last minute. High-level talents but it’s important to say that nobody made money off this project. I think the crew was 12 people in total that followed us in three cars, setting up shots, interviewing people in towns we biked through. This changed the dynamic from other rides we’ve done, but we all knew the film was a big part of the project.

What were the biggest challenges?

EG: Well I’m a big guy. I was the heaviest and tallest guy. I’m 6’3” and was like 250 pounds when we started. It was hard for me to keep up at times, especially on the big climbs. These guys are fast and fit so keeping up was challenging. Doubted myself a lot that I could finish it. I don’t think I would have by myself, but that’s why it’s great to ride with a group. I wanted to inspire other big guys out there that they can do stuff like this, too. People that look at a bike and think they can’t ride because they are big. Bikes have helped me get healthy. They changed my life.

BS: The biggest challenge for me was scheduling everything with the film crew. Just trying to keep everyone happy. This was pretty constant. I learned a lot and would do a lot differently next time.

Have you seen anything like this?

EG: No, not really. It’s always white guys doing big rides in adventure films. Rapha rode Route 66, which is a similar distance but they are all white. Nothing that’s big miles on bikes with all people of color.

BS: Nothing as real and raw as this crew. The difference with this film is that we’re all real cyclists. We all work in shops, race local events, or work as messengers. We talk like that. It’s not a pro Rapha race video. This is gonna be real. Positive of course, but edgy. It won’t be what the cycling industry is used to.

What’s the plan with the film?

BS: The plan is for it to come out in eight or nine months, roughly around June or July, 2021. We’ll try to premier at a few different places and we’re working with brands to help distribute it. For now we’re just trying to keep giving back by going to inner-city areas and teaching kids how to ride and giving away bikes. We’ve been lucky to get a lot of support doing this. It’s been fun teaching kids how to bike tour, or mountain bike, or just basic bike maintenance. Teaching them it’s not about being the fastest—it’s about having fun. This film is meant for that kid that comes from the hood looking for an outlet. A kid looking for freedom. It’s not a film for a kid with a full-ride to college. We want to show cycling is an escape.

What brands supported you?

BS: We got help from a lot of folks: Cannondale, REI, New Balance, Eagle Creek, Pearl Izumi, Lazer Helmets, Easton Cycles, Ringtail, Backroads, Clif Bar, Jaybird, and SRAM, to name a few. I know I’m missing others, too.

What was your goal?

BS: Honestly, just to teach. Really that’s it. If I see young kids like myself I want to give them the inspiration to start riding. If you’re a young kid who’s never owned a bike I want to help get them started. To inspire and show them that no matter where you come from you can ride and feel free.

from Men's Journal https://ift.tt/3nibkGP

0 comments