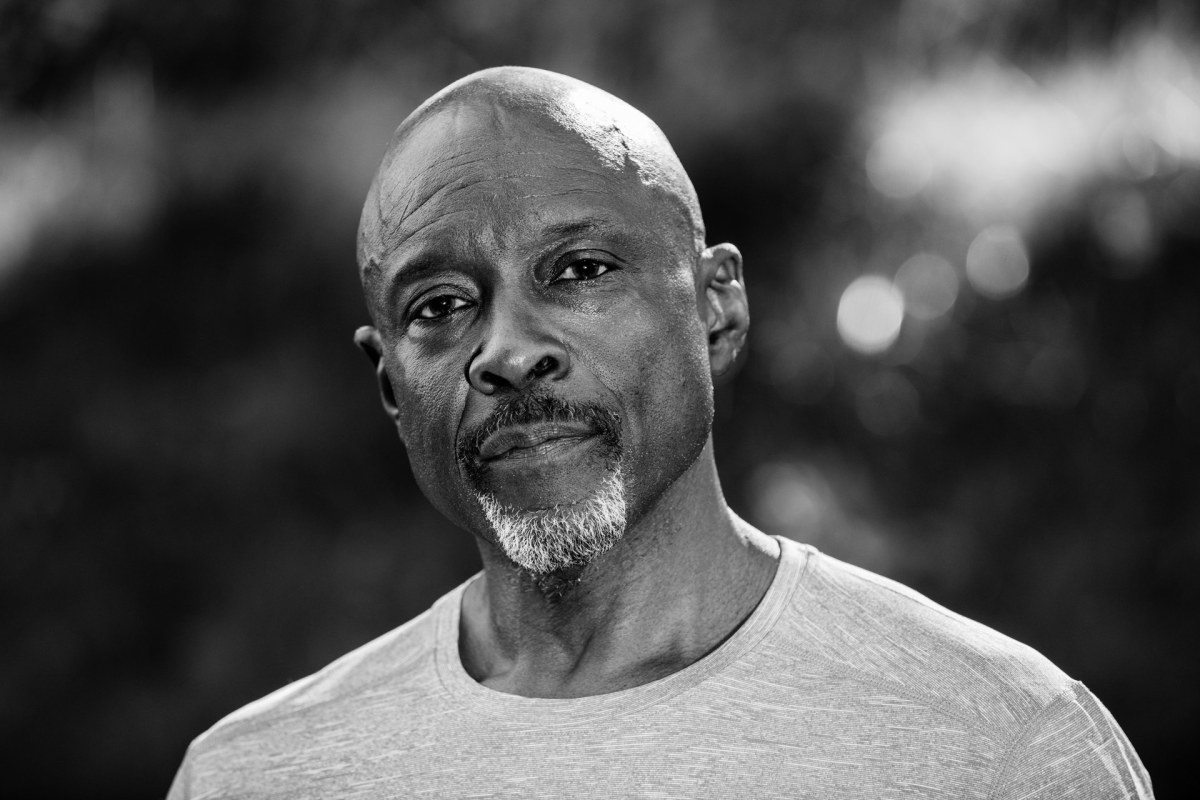

Anthony Taylor didn’t start working for justice last month, when Minneapolis exploded in response to the murder of George Floyd. Sure, he, his wife, his 15-year-old son and 10-year-old daughter were fixtures at protests throughout the following weeks, but the business consultant, youth educator-activist, and Parks and Open Space Commissioner for the Twin Cities’ Metropolitan Council has pursued justice for years in a less expected context: the great outdoors.

Taylor, 61, first learned outdoor mentorship as a counselor at a Boys & Girls Clubs overnight camp his parents sent him to each summer to counterbalance a largely urban upbringing in Milwaukee. Today, Taylor is an avid mountain biker, paddler, fisherman, snowboarder and cross-country skier, as well as an accomplished cyclist who helped found the Major Taylor Bicycling Club of Minnesota and serves on the League of American Bicyclists’ Equity Advisory Board as well as the board of the National Brotherhood of Skiers.

In Minneapolis, Taylor advocates and develops programming that delivers the city’s world-class outdoor opportunities to underserved youth. He is the co-founder of Cool Meets Cause, an outreach program that teaches girls from North Minneapolis to snowboard in one of the country’s largest urban parks, Theodore Wirth. The park’s trails and programs are managed by the Loppet Foundation, where Taylor served as the Adventure Director.

Taylor has experienced first-hand the power of outdoor sports as a tool for youth development; he’s also experienced first-hand the institutional racism that is found in outdoor communities as much as anywhere else in the U.S. He has a clear-eyed view of how segregation designed to “control Black bodies in public spaces” persists in a legacy of disparity between who has access to the outdoors, and who may reap its benefits free from the fear that pervades much of the Black, Indigenous, and people of color (BIPOC) experience in our country today.

An engineer by training, Taylor approaches the twin challenges of racial justice and equal access to the outdoors as a series of inputs leading to outcomes. Sometimes those outcomes are etched into the collective consciousness, like when a Black man suspected of a petty crime is killed in broad daylight by unchecked police brutality. Sometimes, the outcomes are more insidious, like when he and his daughter returned to their campsite to find a noose hanging over the tent. Progress is found in identifying and fixing the inputs that lead to such oppressive outcomes.

With the protest movement that was born on the streets of Minneapolis settling into a steady demand for change across the nation, we caught up with Taylor to learn how this moment is impacting the work he began years ago.

MEN’S JOURNAL: How has access to the outdoors informed your experience as a Black man in America?

ANTHONY TAYLOR: We grew up in Milwaukee, but my mother sent us South every summer until we were 11, to be with my grandmother in Mississippi. We had chickens, a pecan tree in the backyard and a fresh garden, and she grew hogs every year. Those people were connected to the earth. And it was an active strategy; when you live like we did in the urban environment, there was a sense of concern for safety—that was real—so they also sent us to camps.

There’s a disconnection between Black people and the outdoors. That’s new, because I grew up in a community where Black people were deeply grounded in the outdoors; they had just moved from Mississippi or Arkansas or Alabama. They hunted. They fished, and they planted gardens.

I didn’t want to be connected to it because it represented the old ways. We don’t often think about Black communities as immigrants, but we were. We moved to the northern cities. There was a new way of being and we wanted to be that new way. We were kids coming up. Then, especially the ‘70s, movies began to solidify this image of the urban Black experience and urban style and the music. Even today, “urban” and “Black”—you can substitute one for the other. That is a relatively new occurrence.

“Black bodies in public natural spaces have always been managed and controlled.”

Is that urbanization why that connection with the outdoors fell off?

There’s now a bigger disconnection between the identity of Black people connected to nature and the outdoors, and the identity as an urban being. Simultaneously though, there’s been a consistent clarity in institutional America around creating separation in public spaces. Really the first great race riot documented, aside from the Gangs of New York Harlem stuff, was in 1919: There was a race riot in Chicago that was started because a Black child crossed an imaginary line in Lake Michigan into the white beach. Black bodies in public natural spaces have always been managed and controlled.

Being outdoorsy seems like a core part of your identity. How were you able to reconnect and become an outdoors professional and athlete?

One of the instincts of the communities we grew up in is to build more community. So, I started biking, because I’m too small to play football in college. Then, the first thing I do is I meet another Black cyclist who’s older than me, who mentors me. And what did we do? We started a Black bike club. Then, with Black bike club, we go camping on bikes. The nature of outdoor experiences is all about this idea of progression and challenge, and progression and challenge. That’s what we do.

So, then it becomes biking 100 miles in one day, then it’s biking 250 miles in one day, then it’s biking 350 miles in two days, then it’s biking from Colorado to Minneapolis. This thing in me just keeps growing and it keeps feeding me and connecting me to communities that are bigger and bigger and bigger.

And then I start coming full circle in terms of youth development, community development and in terms of health and equity. This is a community that makes significant investment in outdoors, regional parks, state parks. And all of those things are designed to benefit the building of community, family, health, resilience—humanity. And Black people, brown people, poor people need to realize the benefits of that experience as well.

What’s your take on how the community has mobilized in response to the killing of George Floyd?

If you’re under 30, you’ve always known social justice—even from just looking at gender equality, looking at race, that the idea of being an ally is something that is part of that generation. That’s who is out there making this happen. And this is a generation of Black and white children, their social reality isn’t so segregated. And I say that meaning in a very simple way: There is much more integration in the music they listen to, the things they observe on TV, the way that they dress, the way that they socialize, the places they go—living with a lens of social justice in their own lives in the backdrop of institutional racism.

These young people have a reality that really is different. I saw this first with Jamar Clark when Black Lives Matter emerged. From that moment here, I already saw a way that the white supporters were stepping back, were playing an ally role. There are many examples of that.

Now, I don’t have that many examples of that in the outdoors movement. In some regards, [the outdoors movement] has a philosophy that we just need to get everybody to assimilate. If we all wear the same shoes and the same vest we can all get along. Because all of a sudden, if you’re in a canoe, in a vest and the right shorts, you’re not really Black. [laughs]

The outdoors community likes to celebrate itself as a judgment-free place where you can express yourself. Do you feel it needs to make a more conscious effort to ensure everyone can get there?

People don’t get the idea about feeling welcome and feeling safe. Because I’ve had conversations with my son about the police but, honestly, I have a greater fear for his interactions with white people that just break his heart. He’s grown up in the Twin Cities and the white community is so dominant. My son paddles, mountain bikes, snowboards, skateboards—these are dominant white environments. And what I worry about are the times when my son is at a snowboard camp with a whole bunch of kids in Colorado, 1,200 miles from home. And he’s with good friends and all of a sudden, kids start wrestling and out of the blue, a kid in the background yells, “n—– pile!” Or, they’re on a mountain. And the backpack they have on breaks, so they get creative. They rip off one of the buckles that’s on the zipper on the front of the backpack, tie the strap together. And now they’re ready to go and somebody goes, “Oh dude, you n—– rigged that.”

Are these real things that happened to your son?

Those are real things that happened to me.

Those are real things that happen to Black kids every day. And when we talk about putting kids in safe spaces, there’s something that Black people often understand: They feel like white people can’t be trusted to not do things that break people’s hearts.

Just last year, we went to Mount Hood. My family stayed in a hotel and my daughter and I decided to do some camping. Found a beautiful scenic lot. We set up the tents. We left to go back in the city to get some food and let my wife know what we were doing. When we came back, there was a noose hanging in our campsite.

Here I am with my 9-year-old daughter who sees a noose hanging in our campsite. In Oregon. We’re 2,000 miles from home. And I now have to make a decision of, “How do I mend this?” so she’s not frightened for life, so that I’m not running away. And that is real.

So, I said to myself, “I’ve got to replace these memories. I’ve got to change the emotional energy.” Deep down inside, I’m going, “There is no way in hell we’re staying at this campsite.” I immediately said, “Let me tell you a story.”

I told her a story about my grandmother living in Mississippi, fighting for her rights and refusing to back down. As a foundation—that’s what our people did, and that’s what we do. I said, “We have to take this space back.” I told her that Native Americans do something called smudging; Africans, tribal people in New Guinea and the Aborigines in Australia—Black and Brown people all over the planet have a practice of using smoke to cleanse, to purify, to claim.

So, that’s what we’re going to do. You grab that fern and that fern, and we’re going to light them and reclaim this space. And then we’re gonna make s’mores.

I got her to fall asleep in the tent, in a sleeping bag, and I carried her to the car and got the hell out of there.

When we start talking about public parks, public spaces, the challenge is that—broadly speaking—white people cannot be trusted. Because the trauma and the wounds for Black people are so fresh, so easily pickable. That’s easy, that’s low hanging fruit: “I got an idea, let’s go hang a noose in the camp.” That is so easy for somebody to do, but the implications are traumatic. She saw it. She immediately knew what it meant. The 9-year-old knows the symbolism of this tool of terrorism against Black people. Nine-year-olds don’t need to know that.

“You’re representing all Black people who have ever lived and ever will live.” That’s a lot. At the same time, you go, “If you lose, it doesn’t matter. It’s just a snowboard race.”

As an adult doing outdoor expeditions in white spaces, did you have times where you had your heart broken?

As an adult, I can protect myself, right? When someone says something stupid, I just go, “Dude, that is stupid. Yeah. You’re ignorant. I’m going to ignore that.” I can take it head on. My 15-year-old shouldn’t have to.

When you show up in Colorado, and there are no Black people there except you and your little sister, and you both take first [at the USSA Rocky Mountain regionals snowboard competition], there’s going to be some shit talking. They have to be prepared for whatever comes of that. And then you over-prepare because they also have to be gracious winners. They have to carry the load of the race on their shoulders. They’re representing all Black people.

You put that on your 15-year-old in Colorado when he’s on a trip: “You’re representing all Black people who have ever lived and ever will live.” That’s a lot. At the same time, you go, “If you lose, it doesn’t matter. It’s just a snowboard race.”

Does lack of access to the outdoors and recreation resources contribute to a system of institutionalized racism?

I don’t think that the lack of access contributed to [institutionalized racism]; lack of access is a manifestation of that. And this disconnect from the outdoors is a manifestation of the same tides of urban isolation, over policing, institutional racism, disproportionate inequalities in education and work and jobs. We keep thinking that these things are somehow the thing. And no, they’re not the thing. They’re the outcome of the thing.

The disparities that we see are outcomes. We want to impact the inputs that create the disparities. And equity is an outcome. I want to make sure that we don’t say equity is its own thing.

We want equitable outcomes. You and I want to lose the ability to predict. If we’re sitting at Theodore Wirth Park, having a drink, and we see a mountain biker coming—and that mountain biker has on gloves, full gear, full-face mask, and is coming at good speed—we want to lose the ability to predict that person’s race, gender, family income, history. That is equity. That is an equitable outcome.

That is goal oriented. It’s measurable. It’s real. That automatically gets to the redistribution of resources to achieve equitable outcomes. That’s the crux of what we’re talking about.

How do we fix the inputs?

We have to realize that the soil is tainted; that the lived experience of the people who have been telling us this—it is true. The environments in which we raise families, the environments that we build, these educational institutions—it is all tainted and we have to change. We fundamentally have to dig deep and change that. And that’s really a beginning.

We have to acknowledge structural racism. That is, the normalization of historical, cultural, institutional and interpersonal dynamics that routinely advantage white people producing cumulative and chronic, adverse outcomes for people of color and indigenous people. That is the frame. We have to also reveal where structural racism is operating, where its effects are being felt and figuring out where policies and programs can make the greatest improvement.

The last thing is that we have to provide and distribute resources according to need to achieve optimal outcomes. For the outdoors, it’s policy and strategies that make sure that everyone has the conditions for optimal performance, optimal achievement, optimal experience.

So simply saying, “Hey, the parks are open to everybody,” doesn’t create an equal opportunity.

And it does nothing to impart a sense of safety. The lived experience of the people we’re talking about has proven to them over and over and over again that white people cannot be trusted.

Does the outdoors play a role in achieving justice?

It does if we choose to use outdoors as part of our anti-racism strategy for building great humans. It offers unique and special opportunities for growth, self-discovery, human development, family building, health promotion. The outdoors creates a deep connection to the body. I believe the outdoors creates women who have a different relationship to their body than many sports. That’s why girls need to be outdoors, because we need to save girls from all the things in the world that are trying to make them hate themselves. I want to use outdoors as a counter to all the things in the world that makes Black and brown children want to hate themselves. That is the work.

I am concerned that one of the greatest impacts of white supremacy and institutional racism is that Black and brown people believe they’re inferior. They believe that they have a genetic predisposition for failure.

When I take kids to the Boundary Waters, I’m telling them stories about the stars related to the history of Black people in this country. We’re in the woods, we’re seeing this amazing sky, their eyes have made the shift to see in the dark, and now we tell stories of their peoples coming to this new land and using the stars as a way to understand what’s going on, that the stars were what were used to navigate Harriet Tubman north. That we are on the border of Canada, 100 miles from a destination that supported enslaved people escaping the South. When you put the context of someone’s lived experience and their history and their people in the outdoors, we start to shift what we’re talking about, rather than be visitors in a white space.

What do you think justice looks like?

That we can observe an act against humanity and have faith that other people saw what I saw. And that our community and our society will act accordingly. And that’s what’s missing now. That there are many people who saw that person under the knee, dying, calling for his mother, and some of them literally still had to go, “What did he do?” When you see an act against humanity, it is an act against humanity. And that was an act against humanity.

That’s justice, when we can do that, and we can trust that our community can do that. That we are fundamentally safe in the communities that we live in. I think that justice will show up in policy that’s laid down after this.

What have you learned from a lifetime spent testing yourself outdoors that you would apply toward moving forward to equity and justice?

Never stop pedaling.

from Men's Journal https://ift.tt/2ZiwH1m

0 comments