“My hamstrings were on fire,” says Joe Krolick. “For three days it felt like there were four hands pulling at the muscle from behind. At that point, I had chills and a fever that went up to 103 at times. It was uncomfortable to lie down, so I’d stand or sit. I could only sleep by propping up in a chair and stealing an hour here or there.”

The coronavirus pandemic has rocked modern life like nothing in the last 100 years of human history. Sure, we’re all aware of people who have been sick. Some were not confirmed because of a lack of testing. We know that people have died from it and many have recovered.

But have you talked to anyone who’s had it? How about a fit and healthy 40-year-old who has survived. As Krolick is willing to recount, this seemingly distant disease—one that you’ve heard is only a threat to the elderly, or has only casually afflicted the odd celebrity or athlete here and there—is no picnic in the socially distanced park.

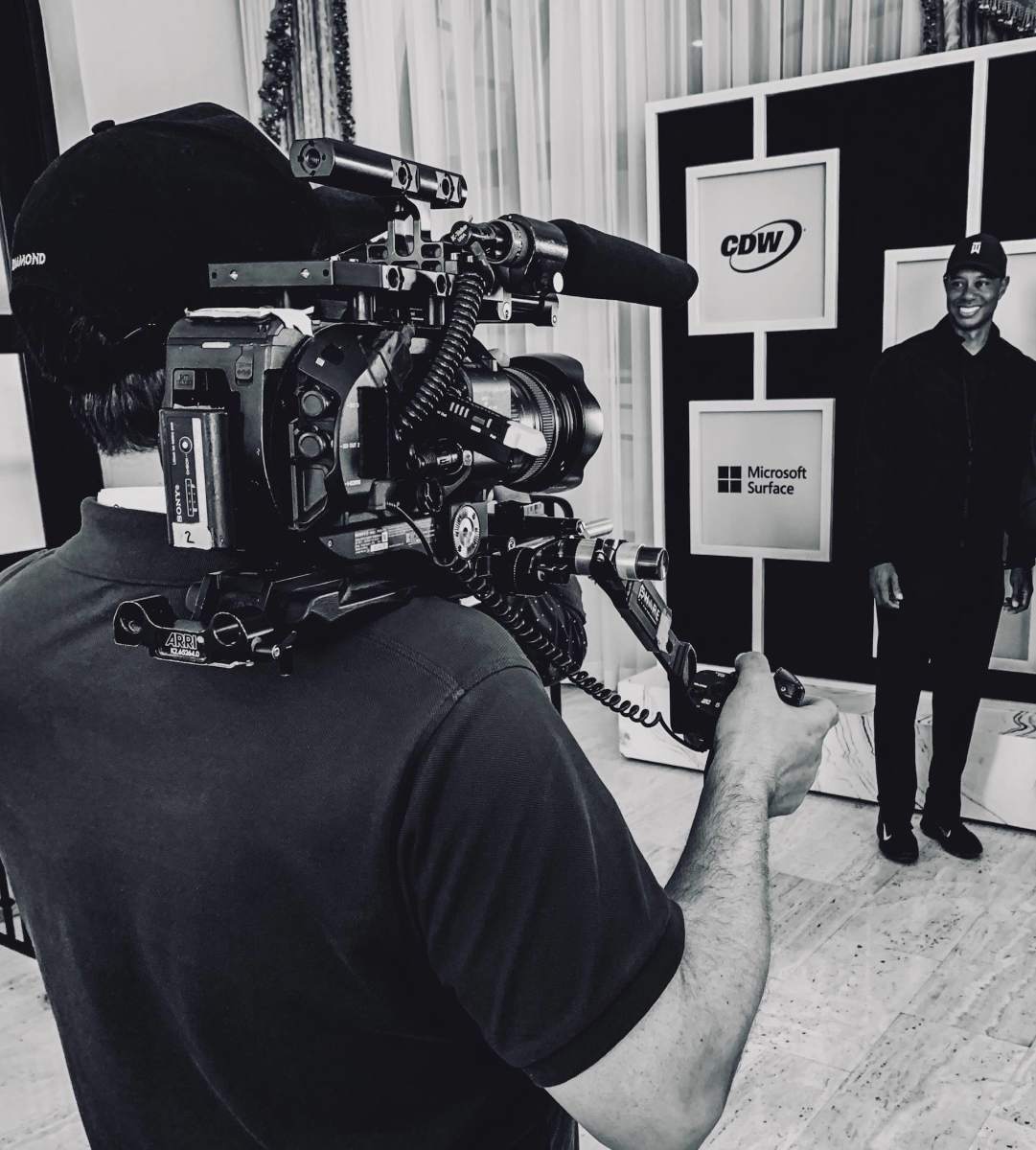

Krolick is a full-time videographer who splits time shooting action-sports athletes and commercial clients. The Orange County, Calif.-based filmer, renowned in the skate world for capturing classic moments, and hailed for documenting the “golden era of street skateboarding,” had spent much of January and February filming the U.S. Skateboard Team, which was headed to the Olympics for the first time (until the 2020 Games’ postponement). He is a husband and a father to a 5-year-old son. He has no major health problems and still actively skates when he can.

Krolick remembers two outings where he could have likely contracted something. One was on March 12, a job filming a Staples Center meet-and-greet between the Lakers (minus LeBron) and employees of the team’s official credit union. The team had released info that two of the Lakers had tested positive but would not identify which players. The other outing was a paintball excursion on March 15 with a friend who’d come down with something.

Krolick’s symptoms started with a tickle in his throat on March 17. He’d been vacuuming the house, so he chalked it up to allergies. But the following day, he woke up with a phlegmy cough and a fever that got progressively worse. Well aware of the pandemic at this point, he decided to quarantine himself on the first floor of his home, away from his wife and son. He called his doctor about a test on March 20. For days, his wife left food on the steps and he remained in isolation, FaceTime-ing his son, who was just upstairs. Krolick was left to reckon with his condition. When the flavor of Lemon-Lime Gatorade seemed off, he learned that loss of taste and smell were common symptoms. The feeling of his hamstrings on fire, however, was still a mystery, the muscular symptom unmentioned in anything that he read about the novel virus.

“I would cough when I took a deep breath,” he recalls. “My nose dried up and I had these crusty, bloody boogers. It was miserable.”

COVID-19’s survival rate at 98-99 percent sure sounds reassuring. But with all that time in isolation, a 2 percent chance of dying starts to haunt thoughts. Krolick sat alone with the din of the media, endless presidential briefings, and the world seemingly falling apart. After two days, he’d had enough.

After his first symptoms, a week elapsed before he could qualify for a test—and only then because he met the criteria of being in contact with someone who had tested positive at the Staples Center, considered a hot spot. Once the excruciating leg-burning sensation subsided, Krolick hauled himself to a drive-through testing station on March 23, administered by nasal swab. He then returned, alone, to his sickbed routine of Netflix and cough.

Four days later, he got the call: positive results. Advised treatment: Take Tylenol.

“They basically said, ‘Unless you really have trouble breathing, don’t call us; we’ll call you.’’’

For the next 12 days, Krolick carried a fever of over 100 degrees with no effective way to treat it. There were nights he couldn’t get warm, as his body temp dropped to 97. There was no team rushing to his aid, no hospital bed waiting with around-the-clock care. He was on his own, and anyone assisting him would have been at high risk of contracting the virus. The Orange County Healthcare Agency did later call, but they only asked a few questions for basic disease tracing. On Day 13, he broke out into a cold sweat and by the afternoon his thermometer finally dropped to 98.6.

Being cautious, Krolick continued to self-quarantine without any symptoms for another seven days before he was finally able to reconnect with his family. All in, he’d spent 21 days in isolation. He’d lost 12 pounds.

Now two months into the pandemic, we’ve all crafted our own rationales of health versus finances, safety versus living our lives, and we’re certainly worn out on everyone else’s. But Krolick’s perspective, as a survivor, carries more weight than empty noise on social media.

“I feel like if the numbers of cases and deaths are still up, why are you trying to open up the economy?” Krolick asks. “Look, I know people have to get back to work. But when people are slightly sick, they’re not going to call out—and then we keep spreading it.”

He’s grown frustrated of seeing people out in groups, not taking it seriously.

“They’re on social media together, talking about social distancing and it’s a joke,” he states, “People aren’t wearing masks. In Asia, wearing a mask in the norm. It’s just common courtesy.”

He spoke to a friend in New York who is certain that he has COVID-19, but feels the need to work in order maintain the job—and its paycheck—to handle the bills.

“I have to work, but I’m lucky that I can distance,” he adds, “People who live in poverty, they have to go to work. They take the risk and it’s a never-ending cycle.”

from Men's Journal https://ift.tt/35XqFVJ

0 comments